Dead reckoning is the process of plotting your position on a chart based on your course and speed from a known point. Of course it's never exact, because you have to estimate leeway and the effect of the tides. But for hundreds of years better sailors than me have used it to cross oceans and I wanted to get better at this skill. I realized how necessary it was on my only attempted long trip on my small boat. I had over estimated my speed and it wasn't until I got a hard fix from points on land using my hand-bearing compass that I realized how necessary getting a better estmate of the vessels speed was. Of course, as my wife informed me, I could just get a GPS. She didn't have any problem finding her way around Florida with her Garmin. The problem is that I'm kind of a nut and want to develop skills that don't rely on electronic devices.

In the age of the Tall Ships, a device called a "chip log" was used to measure the speed of a vessel under sail. This device consisted of a piece of wood, a long length of line and a 28 second glass. The first description of this device is from a book written by William Bourne in 1574 called, "A Regiment for the Sea". Fans of Patrick Obrien can see the device being used in the movie, "Master and Commander".

In the age of the Tall Ships, a device called a "chip log" was used to measure the speed of a vessel under sail. This device consisted of a piece of wood, a long length of line and a 28 second glass. The first description of this device is from a book written by William Bourne in 1574 called, "A Regiment for the Sea". Fans of Patrick Obrien can see the device being used in the movie, "Master and Commander".

So how does this help me? I made a chip log that's how. In the JUL/AUG 2009 issue of Small Craft Advisor there are directions for making a chip log. I made mine out of 50' of tarred seine twine and a triangular piece of plywood I found in my workshop. Basically, rather than having several hundred feet of log line reeling off the stern of my 20' sloop, the article recommends using just 50' of line and a stop watch. It works the same way as previously described, except that we use 50' as the distance measured. Using this method a vessel travelling 1 nautical mile per hour will go 50' in 30 seconds. A vessel travelling 2 nautical miles per hour will go 50' in 15 seconds. I wrote down the distance/speed calculations on the wooden wedge, because I knew I'd forget them anyway.

So how does this help me? I made a chip log that's how. In the JUL/AUG 2009 issue of Small Craft Advisor there are directions for making a chip log. I made mine out of 50' of tarred seine twine and a triangular piece of plywood I found in my workshop. Basically, rather than having several hundred feet of log line reeling off the stern of my 20' sloop, the article recommends using just 50' of line and a stop watch. It works the same way as previously described, except that we use 50' as the distance measured. Using this method a vessel travelling 1 nautical mile per hour will go 50' in 30 seconds. A vessel travelling 2 nautical miles per hour will go 50' in 15 seconds. I wrote down the distance/speed calculations on the wooden wedge, because I knew I'd forget them anyway.

In the age of the Tall Ships, a device called a "chip log" was used to measure the speed of a vessel under sail. This device consisted of a piece of wood, a long length of line and a 28 second glass. The first description of this device is from a book written by William Bourne in 1574 called, "A Regiment for the Sea". Fans of Patrick Obrien can see the device being used in the movie, "Master and Commander".

In the age of the Tall Ships, a device called a "chip log" was used to measure the speed of a vessel under sail. This device consisted of a piece of wood, a long length of line and a 28 second glass. The first description of this device is from a book written by William Bourne in 1574 called, "A Regiment for the Sea". Fans of Patrick Obrien can see the device being used in the movie, "Master and Commander". The whole concept of its use is based on the measurement of a nautical mile. Until 1954 the US considered 6080 feet to be a nautical mile, but the international standard 1.852km is now used. (Most of us use the chart to measure 1 minute of latitude, rather than the scale to figure out a nautical mile). In any event, using a chip log, a vessel travelling at 1 nautical mile per hour would take 28 seconds to travel 47' 3". A knot in the line would mark the first 47' 3". A vessel travelling at 2 nautical miles per hour would travel 94' 1/2" in 28 seconds. 2 knots would be placed at this second 47' 3" and so on down the log line. This is why we use the term knots, because literally sailors used a knot to measure distance and speed.

So how does this help me? I made a chip log that's how. In the JUL/AUG 2009 issue of Small Craft Advisor there are directions for making a chip log. I made mine out of 50' of tarred seine twine and a triangular piece of plywood I found in my workshop. Basically, rather than having several hundred feet of log line reeling off the stern of my 20' sloop, the article recommends using just 50' of line and a stop watch. It works the same way as previously described, except that we use 50' as the distance measured. Using this method a vessel travelling 1 nautical mile per hour will go 50' in 30 seconds. A vessel travelling 2 nautical miles per hour will go 50' in 15 seconds. I wrote down the distance/speed calculations on the wooden wedge, because I knew I'd forget them anyway.

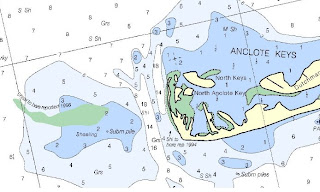

So how does this help me? I made a chip log that's how. In the JUL/AUG 2009 issue of Small Craft Advisor there are directions for making a chip log. I made mine out of 50' of tarred seine twine and a triangular piece of plywood I found in my workshop. Basically, rather than having several hundred feet of log line reeling off the stern of my 20' sloop, the article recommends using just 50' of line and a stop watch. It works the same way as previously described, except that we use 50' as the distance measured. Using this method a vessel travelling 1 nautical mile per hour will go 50' in 30 seconds. A vessel travelling 2 nautical miles per hour will go 50' in 15 seconds. I wrote down the distance/speed calculations on the wooden wedge, because I knew I'd forget them anyway. Using the methods of sailors for the last three centuries, I'll check my speed using this device once every 30 minutes on a long trip, noting the compass course at the same time, then plot this on my chart. I'll report back how this goes during my next foray to Florida.